Policy and Legislation

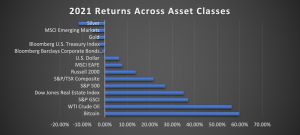

Monetary and fiscal policymakers globally have been incredibly accommodative during the pandemic. The main objective was to keep demand stimulated. Central banks injected record money supply into the markets through 2020 and 2021. US M2 money supply has risen by over 40% in two years. This acted as a major tailwind in the broader commodity market, while dampening low-risk investments such as government Treasuries and Bonds.

Come 2022 and the stance of central banks has changed. With inflation maintaining an upward trajectory, the Federal Reserve began looking to tighten their asset purchases and raise interest rates. The dampening effect of such decisions can take the wind out of the sails for commodity prices through the year. On the other hand, policymakers will need to move cautiously, so that credit availability is not hampered. Here’s a look at the 2022 outlook for the most popularly traded commodities.

Oil

Oil prices are at the core of the super-cycle conversation, as they spill over as the input cost of extraction, movement, and utilisation of other commodities. The Joint Technical Committee (JTC) of the OPEC+ projects a small surplus in oil production this year. However, the cartel has not altered its plan to gradually take production back to the pre-pandemic levels. It has already reintroduced 6.4 million barrels per day (bpd) of the 9.7 million bpd clawed back in 2020. ING analysts expect the increased supply to provide a cap to oil prices this year.

However, that doesn’t complete the picture. Oil producers are far from being daunted by reports of demand being marginally lower than production. The JTC estimates that stockpiles in the advanced economies are 85 million barrels below their 2015-2019 average.

Moreover, there are serious doubts about the ability of the OPEC+ members to meet their production targets. After all, they fell 40% short of the December production target. Amrita Sen, chief oil analyst at Energy Aspects, expects members to add only 130,000 bpd and 250,000 bpd in January and February, versus the target of 450,000 bpd. No doubt, some of these shortfalls are related to force majeure events in Libya and Nigeria. But what’s more worrying is the difficulty faced by Russia, the group’s second-largest producer. Notwithstanding the country’s pre-pandemic comments of “out pumping” Saudi Arabia, Russia was unable to ramp production in December, delivering only about half its permitted increase. The shortfall resulted from a lack of spare capacity in oil pumps globally. In an industry plagued by underinvestment and production stickiness, only UAE and Saudi Arabia can pump out more barrels than they did in January 2020. Despite urges from the White House, the US shale industry’s production stickiness has also dampened expectations of rapid supply growth.

Bloomberg projects the spare capacity of OPEC+ to fall to 2.3 million bpd by summer, which is the lowest since 2018. And, oil demand typically peaks in summer, led by vacation driving and the use of air conditioners globally. Goldman Sachs has a more conservative estimate of 1.2 million bpd, representing about 2% of the world oil market, which is eerily similar to the situation in 2008, when comparable reserve percentages drove oil prices to $147.

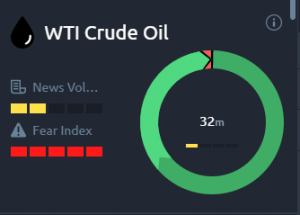

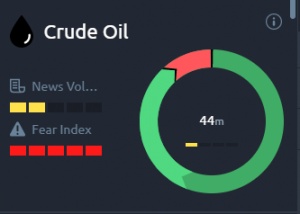

Meanwhile, demand has continued to expand, despite the virus strains. The International Energy Agency expects demand to rise by 3.3 million bpd in 2022 and match the record levels of demand (99.5 million bpd) in 2019. So, while demand returns to pre-pandemic levels, supply lags. This combination is primed to propel oil prices into the triple digits, at least up to a point where demand begins to erode. This is reflected in the longer-term contracts in the futures market as well as in the overly positive market sentiment as seen on the Acuity Trading Dashboard.