Today, some analysts fear a similar story unravelling in Europe. Two of the continent’s biggest banks, Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank, have triggered concerns amid a possible recession. Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank have both seen their share price tumble, by 56.28% and 39.52% year to date, respectively. The Credit Default Swap (CDS) spread, the price of insurance against a security default, for Credit Suisse hit a record high on October 3, before easing the next day after the bank announced a debt buy-back programme.

What’s Happening at These Banking Majors?

Credit Suisse has had a scandal-ridden few years. These damaging, and ultimately costly, scandals include the high-profile failure of investments in Greensill Capital and Archegos Capital, as well as a guilty verdict for Credit Suisse’s inability to prevent money laundering by Bulgarian drug traffickers. Credit Suisse CEO Ulrich Korner has insisted in a leaked internal memo that despite its legal troubles and whispers of a collapse, employees should not be confusing day-to-day stock performance with the bank’s strong capital base and liquidity position.

Deutsche Bank has been similarly reiterating the strength of its position. The German bank has recently completed a long-attempted restructuring effort, delivering a cost-cutting program that analysts expect to be successful.

The crux of the wider market fear is that, like Lehman in the noughties, the collapse or the constant shrinking of institutions like Credit Suisse and Deutsche Bank may lead to a contagion effect, resulting in more high-value failures. On the other hand, these banks are more than four times the size of Lehman at its failure.

Who Could Lose in a European Banking Crisis?

A banking crisis is when multiple financial intermediaries in an economy experience serious solvency or liquidity problems at the same time. When depository institutions fail, the first line of panic is formed by the depositors. A panicked depositor base, especially with recessionary fears brewing, would prefer to have their deposits in hand rather than at a bank facing the risk of failing. This causes a worsening of the crisis. Banks that are the largest in the economy they serve, such as Nordea in Finland, represent a higher risk of default once such a crisis begins to unfold.

Dutch financial services firm, ING, is among the European banks that are most sensitive to interest rates. There has been significant short interest in ING of late, after the firm said that profitability in its lending business had declined due to tighter net interest income. Banco Santander’s margins are already under pressure due to higher taxes imposed on banks by the Spanish government, which aims to generate around $7.02 billion over the next couple of years.

Germany’s 10-year yield, which is considered the benchmark for the euro bloc, has risen from below the closely watched 1% level on August 1 to more than 2.4% as of October 12, hitting its highest level since August 2011. Britain’s 10-year Gilt also reached near a 14-year high on that day. Despite high inflation, bond yields in Europe could fall, with investors expecting the ECB to refrain from aggressive monetary tightening in the face of a recession.

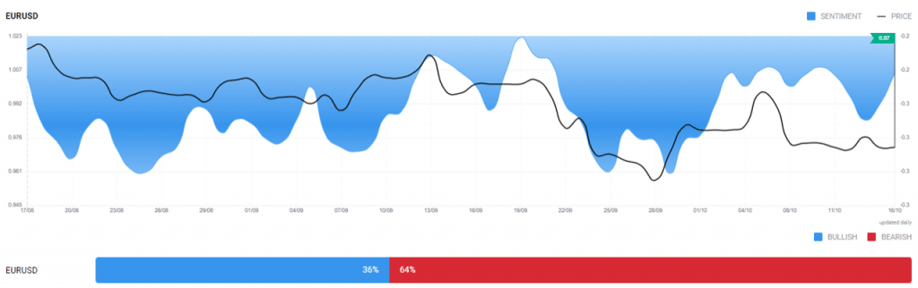

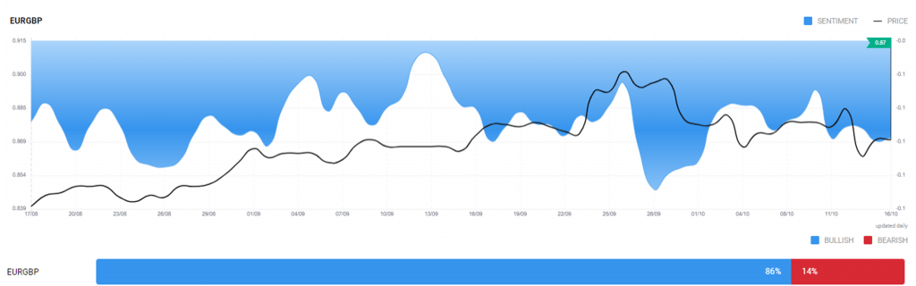

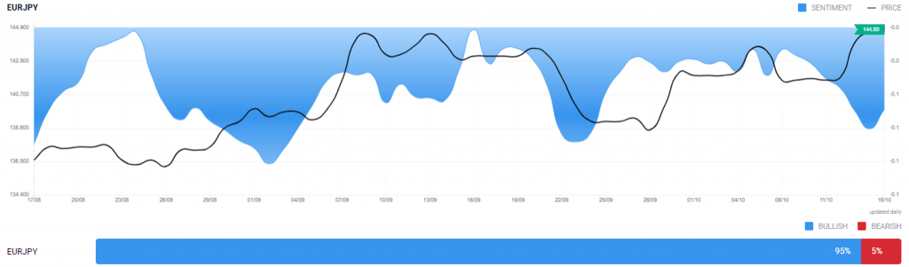

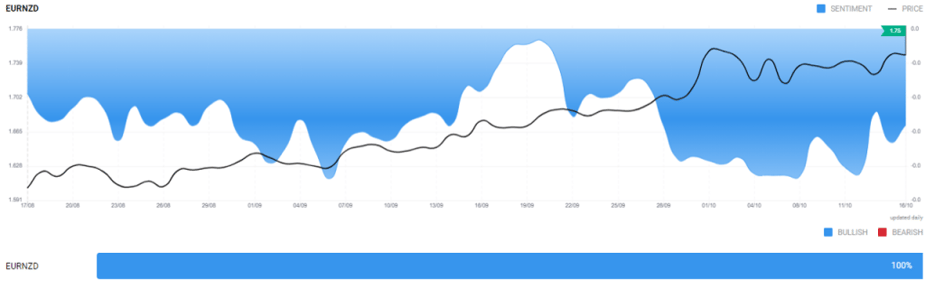

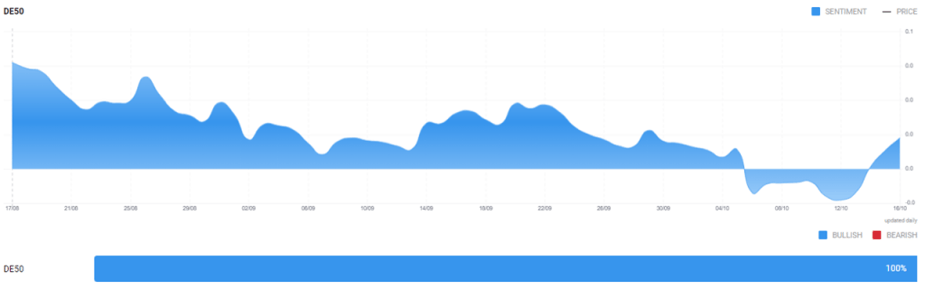

The euro will also probably not shine amid a potential banking crisis. The ECB is already unable to out-hawk the US Federal Reserve. The difference could widen, shaving off the euro’s power in currency carry trades. The Acuity Trading Widget reflects a more favourable sentiment for the US dollar versus the euro.